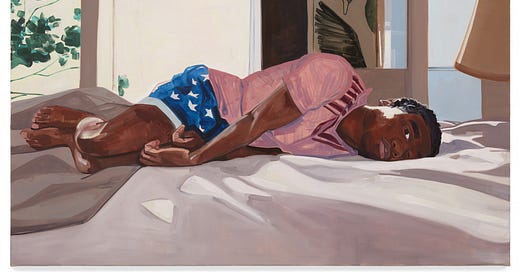

Vigil By Tajh Rust

"What need is there to weep over parts of life? The whole of it calls for tears.”- Seneca

Therapy wouldn’t be my first recommendation to someone who came to me with a problem, but I wouldn’t discourage it either. It depends on the problem and the person. That said, I’m sceptical of the common retort, ‘seek help!’ since it often just means, ‘go to therapy.’

In some online circles, it’s become all the rage to dismiss talk therapy as useless, effeminate psychobabble. That view, however, isn’t one I share. Anyone who believes this isn’t considering all the disturbing, unsavoury, and taboo things that can torment the mind, things that are unspeakable to anyone who isn’t paid to listen.

But I started thinking about the effectiveness of talk therapy when a close friend, struggling with infidelity, shared her experience seeking professional help. After a few sessions, her therapist simply said, “maybe you’re polyamorous.”

When she told me I was stunned, not by the revelation but by the ease with which it was offered.

Indeed, more people are exploring a version of non-monogamy. My issue isn’t about whether polyamorous relationships are good or bad. My problem is how the suggestion risks functioning as a justification rather than prompting deeper self-exploration.

Had my friend walked into her therapist’s office saying, ‘I enjoy cheating and wish it wasn’t culturally frowned upon,’ her story wouldn’t be included. But she was distressed, ashamed, and confused about betraying the one person who understood her. If my friend had been questioning monogamy, the suggestion would’ve made sense. But she wasn’t trying to justify her actions—she was trying to understand them. A more thoughtful approach would have explored why she kept cheating despite her guilt. Was it validation? Sabotaging the relationship? Fear of intimacy? These are the kinds of questions that could have led her to real clarity. Instead, she walked away with a label that, while a comfort to some, may only be a cover for others.

This therapist is not representative of all, and perhaps my friend’s retelling left out some key details. There are a variety of helpful therapeutic approaches, but given the widespread fear of public backlash, some therapists may feel pressured to validate choices rather than interrogate them.

My friend’s experience made me think about personality types, and how different that conversation might have been with someone less inclined to question their own motives. Fortunately, my friend was just as taken aback by the polyamorous suggestion as I was. But it dawned on me that certain personality traits might actually work against the effectiveness of talk therapy.

In the midst of thinking about this, a month ago, I finished watching The Sopranos for the first time, a show that largely sustained my interest due to the charged relationship between mafia boss Tony Soprano and his impeccably dressed psychoanalyst, Dr. Melfi.

Against the advice of her own therapist, and despite Tony’s aggressive outbursts, a mix of morbid curiosity and unspoken romantic tension compels her to keep him as a client. However, the patience of Dr. Melfi’s therapist eventually runs thin. In an attempt to make her stop seeing Tony, over a dinner party, he brings up a study suggesting that talk therapy may actually help sociopaths become better at manipulation rather than rehabilitating them.

Later, we see a frantic Dr. Melfi poring over the study, anxious to determine whether her years of effort to help Tony have been in vain. And judging by her subsequent actions, it’s clear the contents of the study were persuasive.

While The Sopranos is fictional, studies like the one referenced in the show do exist. This reinforced my suspicion that talk therapy may not suit all personality types, and I have a bigger hunch this extends beyond conditions like narcissism, sociopathy, and psychopathy. For one, you don’t need to meet the diagnostic criteria to exhibit traits commonly associated with them. And those same traits, as well as others, can significantly hinder the effectiveness of talk therapy.

For instance, paranoia, defensiveness, projection, and poor comprehension can heavily distort our perceptions. There is a degree to which therapy relies on accurate communication. But if someone’s struggles skew their reality, they may unknowingly present a false version of events. The therapist, working with this information, might then offer guidance based on a misrepresented situation.

Instead of gaining clarity, a client might walk away with insights that reinforce their misinterpretations. A skilled therapist will, of course, ask probing questions to uncover a clearer picture of events. But there is little to nothing that can be done if the client is committed to the story in their head.

This is not a criticism of therapy, but a recognition of its limitations. Therapists are humans, not magicians, and our species is far too messy to outsource self-understanding to a single source. It’s also easy to imagine a legion of weary therapists out there, silently wishing some clients wouldn’t place the entirety of their recovery in their hands. Indeed, there is only so much that can be done in 50 minutes per week. But when it’s clear how many people scoff at the idea of dating someone who hasn’t been to therapy, and others sigh in relief upon knowing that someone has racked up a few hours in the well-worn seat, our view of what talk therapy can do, needs re-adjustment.

Moreover, the idea that only therapy can foster self-awareness feels too elitist for my liking. I believe in the power of community efforts and, though it’s often put to the test, I can’t help but think we, as individuals, are far more capable than we often realise.

Beyond the go-to-method, therapy comes in many other valuable forms. However, there are four key support sources we should take just as seriously, ones to be explored from right where we are, with little to no expense, that demand our attention.

This isn’t an extensive list, but this piece is already longer than I intended, so I’ll cover more in a future post. The following is based on experience, reflection, and the stories from close friends. These are things we already know but could benefit from seeing in a new light.

Mentoring:

First up is mentoring. I’ve noticed that I’ve never wanted to dissect my childhood and the perceived failures of the adults in charge, as much as when I’m confronted with a creative task I find difficult.

Inner turmoil often arises from blocked creativity or unfulfilled callings, which can be redirected into more destructive or numbing behaviours—things that give us the momentary high of achievement such as; retail therapy, procrastination disguised as research, but lack any long term satisfaction.

Creative or meaningful work won’t solve all of life’s problems, but it can provide a sense of fulfilment and satisfaction that far surpasses the tranquillising effects of distraction. But when we continue to resist doing what we ought to, self-doubt, and a pervasive sense of inadequacy takes hold. But resolving it may not come from exploring how our parents failed us, bullies tormented us, or lovers betrayed us.

We often fixate on these past hurts to make sense of why it’s so hard to do what is important today. And while these historical pains are significant, they can keep us focused on the origins of our pain when what we really need is someone who won’t only listen and question, but guide us through the unknown.

That person can be a mentor. In my view, while it helps, a mentor need not have already walked the path that you’re stumbling on. What matters most is that they possess the traits, talents, and skills to succeed in your chosen field.

After therapy we’re left to our own devices until the next session, often left reeling from whatever has just been uncovered. Unless you have deep pockets, you can’t call, text, or email the moment the issue rears its ugly head again. A mentor, on the other hand, offers a little more flexibility. While you can’t expect them to be available on demand, they’re likely to check in, request updates, hold you accountable, and maybe even reply after hours.

You may not need to look far for mentorship, someone you already know and respect can provide valuable feedback. It can be as simple as asking for their perspective on a situation or seeking advice on a decision. You might be surprised at how flattered they feel to know that you regard them as someone whose guidance you value.

There are two people in my life that I run every wild idea, half-baked theory, and restless questions by. They challenge me. They ask tough questions, and aren’t afraid to tell me when I have an idea that is batshit. They don’t just offer emotional support; they offer practical guidance that helps me move forward.

And just like that, as progress unfolds, the impulse to dissect my early years diminishes. The childhood I once saw as marked by criticism is now understood as necessary discipline.

Where we often seek therapy to make sense of the past, mentors without being dismissive encourage us to act in the present. They see potential where we see inability. They push us to move forward when we feel stuck. They believe in us even when we don’t believe in ourselves, and perhaps most importantly, they’re unlikely to glance at the clock, just as we’re on the verge of an emotional breakdown.

Support Groups:

Over the years I’ve been incredibly close to people for whom talking about feelings, emotions, the past, and their present problems, leaves them flustered, panicked and overwhelmed until the words collapse under the weight of what they’re trying to reveal.

In a bid to help themselves, some of these people have considered therapy, and it’s silently struck me that they’d likely have to pay thousands before they even scratch the surface. The sort of money, none of them had.

Support groups often cover a wide variety of issues, and finding one that suits your needs is often easier than you might think. One friend, for example, was able to find a self-harm support group with just a quick Google search. She invited me to sit in during one session. She never spoke, nor turned her camera on, just as she hadn’t in the previous weeks, despite showing up to every session. But hearing others speak did something useful. Witnessing people from a myriad of backgrounds, across age and social standing, made her feel less isolated. The other benefit was hearing from a range of voices, rather than a single perspective from someone who’d studied the problem but may have never lived it.

This got me thinking about support groups more broadly. For the verbally clogged, the chronically distrusting, and for those who can’t help but spend the entirety of therapy sessions trying to decipher if they’re smarter than the person they’re paying—support groups might be a beneficial first step in the winding road to recovery. Intellectually, we know there is a slim chance that out of 8 billion people, we alone have this particular flavour of misfortune. But the sense that this affliction is ours alone is hard to shift, especially, when you don’t personally know anyone with the same struggles. Support groups are a great way to counter this.

Much has been said about the loss of community, especially for those living in big cities. But community can feel hollow when what plagues you the most can’t be spoken and when the language itself deserts you.

For me, this is the real value of support groups, hearing others give voice to the haunting half-formed feelings you haven’t yet found the language for. These sessions make tangible, what had only existed as a vague, shapeless ache.

Support groups also help with the increasingly challenging task of listening. One might think it depressing to sit in with a bunch of strangers talking of all that ails them. But hearing a variety of stories from many who’ve fallen further, can remind you that you’re not as lost as you believe. It can also serve as a warning of where you might end up if you don’t change direction.

I’m at that age where it’s common to rant about the perils of modern technology, but like most anger, that itself is only a cover story. My real problem is that we aren’t yet anywhere close to using social media to help us with our most pressing problems. Which brings me to my next point— anyone can start a support group. You don’t need to be an expert, all you need is experience in the problem at hand, the patience to listen, and a wifi connection.

In an atomised world, mutual aid and shared suffering might be the most accessible form of healing we have left. It might be time to consider if what helps us survive is not always expertise, but presence. Not fixing or diagnosing, just the willingness to sit in the wreckage together.

Spiritual guidance.

Much has been said about the decline of religion in western culture. Some argue it’s the reason for the erosion of a moral framework, the crisis of both meaning, and mental health. Such people are fond of saying, ‘there are no political solutions to spiritual problems’.

I’m not religious, but I respect the attempt to bind yourself to a set of ideals in a world that encourages the indulgence of every impulse. But religion isn’t the only way to bind oneself to something higher. Especially when some treat religion as little more than an insurance policy in case hell exists. A sentiment, captured, perhaps too cynically in a quote often attributed to David Bowie, “Religion is for those who fear hell and spirituality is for those who’ve been there.”

But there is something to this. Speak to anyone who describes themselves as ‘spiritual’ and you’ll often find the catalyst was bleak. However, spirituality is a nebulous term in the digital age. Too often it conjures up wallet-emptying wellness retreats, exploitative gurus, mania mistaken for mystical insight, and spiritual justifications for the most sinister acts.

But what I'm referring to is more practical than mystical. It’s more like a kind of detached witnessing. Paying closer attention to your own experience, allowing thoughts to pass like speeding cars on a motorway, neither chasing them down nor searching for somewhere to park. It's a loosening of the boundaries between yourself and everything else. It’s less about seeking something out and more about becoming a little more awake to what’s already here.

Naturally, talk therapy is focused on talking and thinking through problems and emotions. However, much of our suffering stems from our entanglement with thought. Detached witnessing can be particularly useful here, especially for those who no longer want to act from their undesirable impulses. The beauty isn’t only in its ability to calm the mind, but the way it forces you to be more honest with yourself. It’s a way of witnessing your own pettiness, cruelty and self-deception without flinching or dressing it up.

Therapy, while offering moments that are revelatory, can seldom, if ever, offer moments of transcendence. The breathtaking instance where you’re no longer chained to your thoughts. Such moments, even if fleeting, are unforgettable, revealing that beneath the mental chatter and fictions regarded as true stories, an enhanced state of being is within reach. Few things change you as profoundly as glimpsing your dormant abilities. It’s the type of flash that can strengthen the commitment to living by certain values, be it courage, gratitude, or patience, not for applause or reward, but because something within us feels truer when we do.

When you’re paying attention, there’s nowhere to hide. It becomes much harder to pretend your lowest actions have some righteous or noble cause. You simply know that you’re being a idiot, and the cover stories previously given for those actions no longer hold. While you’re still capable of being awful, you do it with the full, humiliating awareness that you're being a moron, not some misunderstood truth-teller or righteous defender of boundaries. Paying attention to your own experience offers a different vision of what you might be capable of — and sometimes, that vision is enough to pull you back when you're on the verge of falling short.

Philosophical Guidance

If spirituality helps us step back from thought, philosophy helps us wrestle with the ones that won’t let go, showing that thinking, when done well, can be its own form of relief.

When I was 10 years old, I was introduced to what I consider the greatest rap song ever made, along with my first philosophical insight. In his track Slippin’, DMX quotes Nietzsche: “To live is to suffer, but to survive, well, that's to find meaning in the suffering.” That song broke a dam in me like no other.

In the aftermath of the murder of a loved one, grief watered that earlier seed, causing my mind to turn naturally philosophical, not in the formal, academic sense, (please, don’t ask me anything about Hegel)—but in the way of questioning what drives human behaviour at its most brutal.

In the face of violent tragedies, bitterness and hatred, many would argue are, justifiable, responses. But as understandable as those feelings are, the weight of anger felt self-punishing in a life that could end at any moment.

Grasping how easily the mind can make heinous acts like murder seem justifiable, and facing all the unflattering revelations that arose from watching my own thoughts, I wondered, how could I stop myself from succumbing to my own capacity for destruction?

Religion, wasn’t quite right for me. That’s when I turned to philosophy and found the concept of self-mastery. A tall but worthwhile order. In Taoism, Stoicism, and Existentialism, I found compelling arguments for personal responsibility, self-determination, mastery over desire, and the value of controlling one’s reactions and judgments in the face of external events.

Today, the insights of philosophers remain a steady comfort. Even the bleakest ones carry a sort of wry humour, revealing the absurdity of it all and reminding me not to take myself, or much of anything, too seriously.

Plato described philosophy “as preparation for death”. However, I don’t see this as only about our own physical end, but loss of a loved one, a version of yourself, the collapse of a relationship, the slow draining away of confidence or hope. These are the kinds of deaths that can come long before the final one.

Therapy tends to focus on how to feel better, how to soothe, manage, or untangle the pain, but philosophy can help us bear pain by giving it context. It reminds us that suffering isn’t personal but written into the small print of existence. It helps us grapple with what we loathe to hear, yet must be heard: meaning is built; not found, closure is self-given and there are rooms within you no one, including you, will ever enter.

And many other bitter pills that over time, become more liberating than they first appear. Philosophy teaches us to live with ambiguity, uncertainty and suffering as inescapable parts of the deal. And maybe even how to find something beautiful or dignified in them.

At some point, enormous pain comes for us all. No matter how intricately unique it may feel, it’s as ordinary as sliced bread. If anything is unique, it’s how that suffering is carried. Rather than as justification for nihilism, despair, and misanthropy, it can be met with more grace, wisdom, or acceptance. That’s what philosophy can offer, not a cure, but a set of principles to help you stand more steadily in the face of life's most brutal realities.

Friendship:

I’ve saved friendship until last, because out of all the things I’ve listed, at it’s best, it is the most life-affirming. One of the things that can make all the effort and striving feel worthwhile.

Yet it remains an area of quiet frustration, because all too often, friendships are held together only by the years spent together rather than the depth of the connection.

We often hear that being ‘seen’ is the hallmark of meaningful connection. But maybe its rarity lies in our collective lack of curiosity— a failure to be intrigued by one another, or the tendency to mistake inquisitiveness for intrusion. Too often, we approach conversations, even amongst friends, like a solo game of squash instead of a shared game of tennis.

Despite the endless ways to communicate, good conversation, both political and personal, is fading. In an age that has seen increasing loneliness, we appear to have, as Aristotle would put it, an abundance of friendships of utility and pleasure, built on mutual favours or shared enjoyment, but a scarcity of friendships of virtue, those defined by admiration, respect, and a shared commitment to each other’s character and well-being.

The friend who asks not just “How are you?” but “How are you feeling?” Not just, “What’s new?” but “What’s been on your mind?”

For some, such questions feel invasive, or intimidating as if a deep response is expected. In reality, it is merely an invitation to drop the pleasantries that can make socialising more draining than nourishing. Beneath talk about work, politics, jokes, and gossip, there is often a person who fears they’re barely holding it together or who is one piece of bad news away from coming undone.

What doesn’t help is the belief that sharing personal details, especially those that weigh heavily, is a form of emotional trespassing, a kind of oversharing that risks discomfort. We must choose our friends wisely, as it takes a special person to bear the gravity of real disclosure. But such connections are harder to forge in the digital age. Though we may live in the same places, we increasingly occupy different virtual worlds—worlds in which we absorb information, and beliefs that feel too risky to share. And so, we tiptoe around even those we love, not always resenting them, but the version of ourselves we feel obliged to present in their presence.

Some argue the over-reliance on therapy is a symptom modern friendships. But this isn’t an argument I find entirely persuasive. As mentioned earlier, there are burdens of the psyche too delicate to place in the hands of someone without a legal obligation to confidentiality. But perhaps the growing turn to therapy speaks to something deeper—the weight of living a double life, in search of the kind of connection that, in a different world, friendship might have offered.

Indeed, it’s important to have friends to laugh and escape with, those who may double up as useful contacts. But at its deepest, friendship is a place that can help alleviate the load. It doesn’t eradicate pain, but it helps us manage and gain clarity when clouded. A place where, at last, we can take off the mask.

If we feel like we aren't seen, consider whether you’re afraid of being truly heard. That means to drop the mask of being the funny one, strong one, aloof one, the cool one, and allow yourself, for once, to be the whole one—multifaceted, contradictory, wonderfully complicated, beautifully strange, and yes often, deeply sad.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Unravelled to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.